Liz and I had a great conversation with Scott Cameron for the August 3rd episode of “The Joys of Teaching Literature.” Listen to it here or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Category: writing

CATE Conference 2019

Next week, Liz and I will be presenting at our third straight CATE (California Association of Teachers of English) Conference. This year, our session is titled “Rigorous and Authentic Interdisciplinary Novel Units: Effectively Pairing Literature and Informational Text Standards.”

Here are links to posts about the last two conferences:

Essay on James Joyce and Christmas

I have an essay titled “Holiday Parties and the Dead” up at Connotation Press: An Online Artifact. You can check it out here.

Parnucklian for Chocolate Audiobook

The Audible audiobook of my novel, Parnucklian for Chocolate (first published in 2013 by Red Hen Press), was released last week (June 7th). Here’s a link:

Rethinking Shakespeare’s 5-act Structure

For most of my twelve years teaching high school English, I’ve taught a lesson on the 5-act structure of Shakespeare’s plays.

I even put it in a book.

But I don’t think any of it is right.

Two weeks ago, as we waited in a church pew for our oldest son’s preschool graduation ceremony to begin, my wife, Liz, and I got into a debate about the climax of Hamlet, said debate beginning with my above-repeated admission that what I’ve been saying to students about Shakespeare’s 5-act structure I no longer believe to be true.

What I’ve been saying—off and on for twelve years—and what I also included in a chapter on Taming of the Shrew in our book, Method to the Madness: A Common Core Guide to Creating Critical Thinkers through the Study of Literature (co-written by Liz and me; she wrote the Hamlet chapter), is that Shakespeare’s 5-act structure can be roughly mapped onto the familiar plot diagram as follows:

Act I = Exposition

Act II = Rising Action/Complications

Act III = Climax

Act IV = Falling Action

Act V = Resolution/Denouement

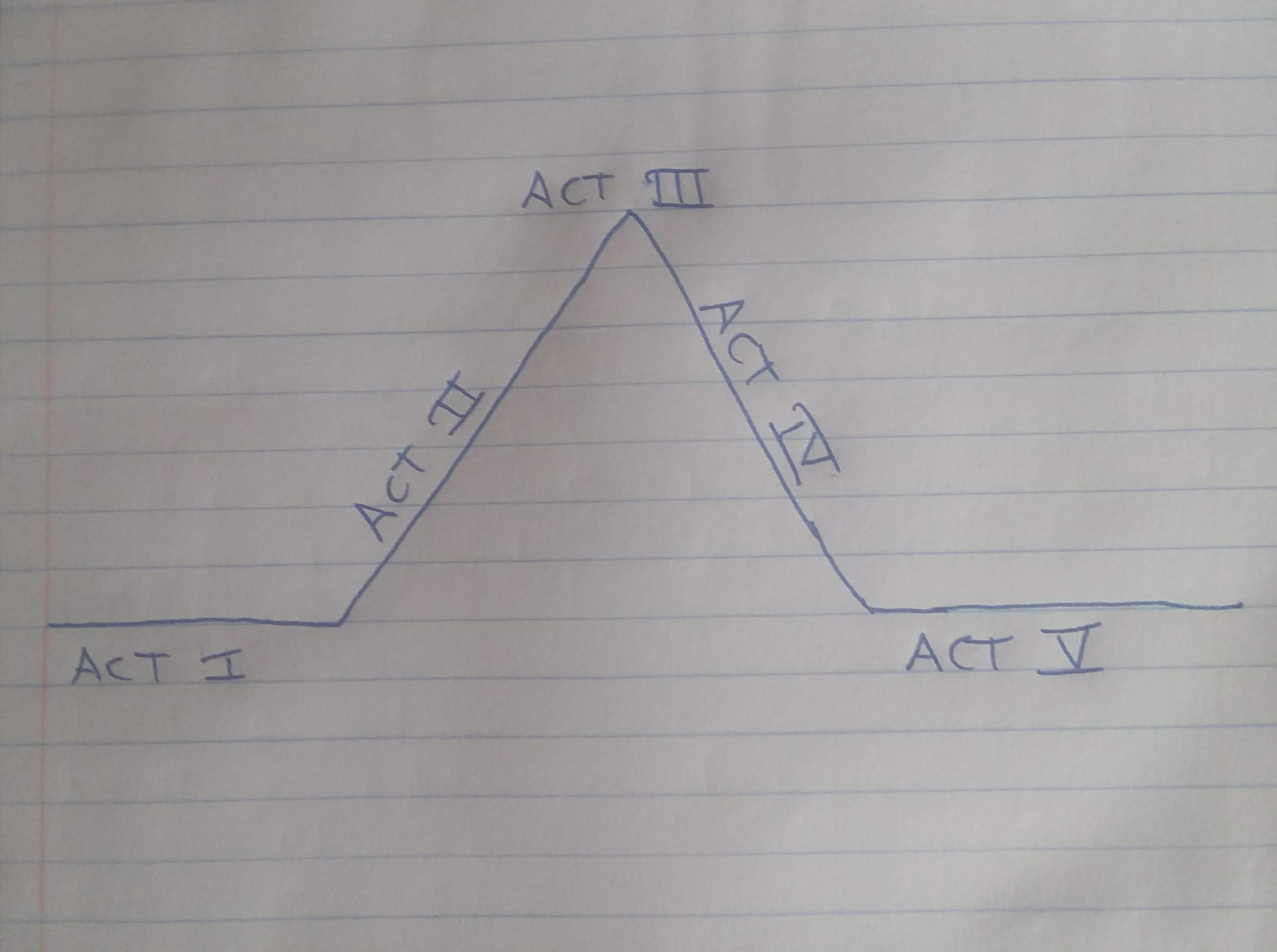

I, of course, am not the first nor the only teacher to teach this. It all started with Gustav Freytag, a 19th-century German novelist and playwright, who diagrammed the five story parts above (exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution) using a triangle, now known as Freytag’s Pyramid, which looks like this:

As an example, Freytag mapped the 5-act structure of a Shakespeare play onto his pyramid (said mapping making its way from Freytag through generations of teachers and teacher resources to me, around twelve years ago, and on to my students, some of whom now teach, and into an additional teacher resource, co-written by me).

The last couple of times that, out of habit, I drew the above diagram on my whiteboard, I knew there was something wrong with it.

This was perhaps because it did not square at all with the diagram I had been drawing for students during my short fiction unit.

About halfway through my teaching career, I figured out that Freytag’s Pyramid, as shown above, is problematic when applied to fiction writing, particularly short stories, and particularly when trying to help students draft well-plotted short stories.

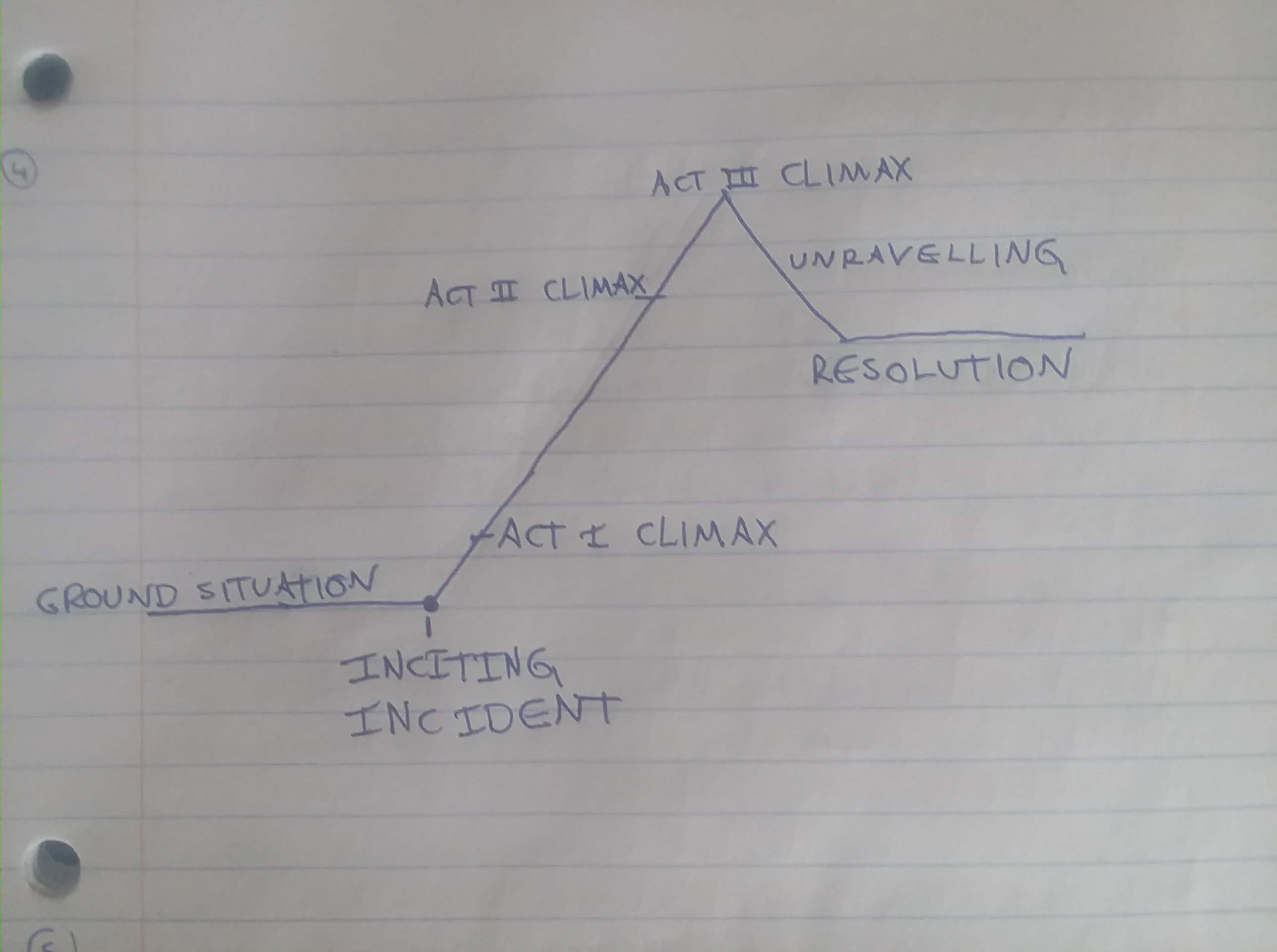

I started drawing this, instead:

The biggest difference between Freytag’s diagram and this one is the latter’s lack of symmetry (reason to follow).

A similarity is that they both begin and end with a flat line.

The flat line on the left-hand side represents the ground situation (I also discovered, about halfway through my teaching career, that I’d been teaching exposition wrong, telling students that it’s the part of the story in which the author introduces the setting, the characters, and the conflict. All of that is true, but what is more helpful to students who are drafting stories is to tell them that the exposition has two vital components: the ground situation [the state of things, often teeming with potential conflict, before the conflict is incited] and the inciting incident [just what it sounds like: an incident, often but not always the addition of a character, that incites the conflict and sends the previously flat-lined diagram angling upward]).

The flat line on the right-hand side represents the new state of affairs after the conflict has been resolved and the knot unraveled.

This post-denouement state of affairs does not/should not/cannot return to the same state of affairs represented by the ground situation. A change must have occurred, otherwise no story has been told, hence the lack of symmetry in the latter triangle (this is not original; it is a modification to Freytag’s triangle suggested by John Barth in his metafictive story, “Lost in the Funhouse” [and probably elsewhere, too, by others]).

The other big difference between the two triangles is the elimination, in the latter, of the falling action, one discovering when studying (or simply consuming) stories that the resolution often comes on the heels of the climax (another reason for the lack of symmetry: there is usually much more story before the climax than there is after it).

What I like to say to students about the above-drawn diagram is that it is a formula that allows for infinite variations. It is inexhaustible. And it is.

I said the same thing to a roomful of teachers at February’s CATE Conference, where Liz and I were leading a workshop on teaching contemporary short fiction.

After I had said the above and had used one too many Pixar movies as an illustration, a participant, as a sort of friendly challenge, asked if we could apply the same structure to “The Flowers” by Alice Walker (a one-page story describing a single incident), which we had earlier in the workshop read on the lookout for concrete details.

I wasn’t prepared for such a challenge, nor had I previously attempted the suggested application, but the clever teachers in the room quickly discovered, despite all of the differences between “The Flowers” and Finding Nemo, that the structure did indeed fit both. Perfectly.

So, then: Shakespeare.

Liz’s and my church pew debate came at the end of a week in which I had listened to dozens of high school juniors, during their oral examinations, explain that the Mousetrap (Hamlet’s play-within-the-play, manufactured to reveal Claudius’s guilt) is the climax of the play.

When, in our pew, I asked Liz what the climax of the play is, she answered that it is the Closet Scene, particularly Hamlet killing Polonius.

The students’ reasons were fuzzy (for many, they were unstated altogether; the reason that was the climax was that their English teacher had said so).

Liz’s reasoning, on the other hand, was fully- and well-articulated (she is brilliant in many many things, but particularly astute when discussing Hamlet): that, to poorly paraphrase, by killing Polonius (believing he is killing Claudius) Hamlet demonstrates the resolution that, two acts later, allows for resolution.

Both the students’ and Liz’s proposed climaxes occur in Act III (scenes 2 and 4, respectively) and therefore fit the Freytag map of Shakespeare’s 5-act structure.

Freytag supposedly leaned heavily on Aristotle, but it is precisely the lessons in Poetics that lead me to question Freytag and my own previous teaching.

Aristotle says that the Complication (what we often call the Rising Action) is a causal sequence of story events (or scenes) in which, scene to scene, the stakes (and thereby drama) increase and increase until we arrive at the climax (which Aristotle describes as a reversal in fortune [bad to good, good to bad, etc.]).

After this final reversal, Aristotle says, there is nothing but the unraveling.

How, then, can this causal sequence reach its peak in Act III, with two acts to go?

From our pew, I argued that the climax of Hamlet is the duel in Act V. It all builds to that. Hamlet dies (final reversal), after which there is only the unraveling (Fortinbras takes over, honors Hamlet, etc.).

Freytag, those juniors, and Liz are right about one thing, though: Act III is climactic.

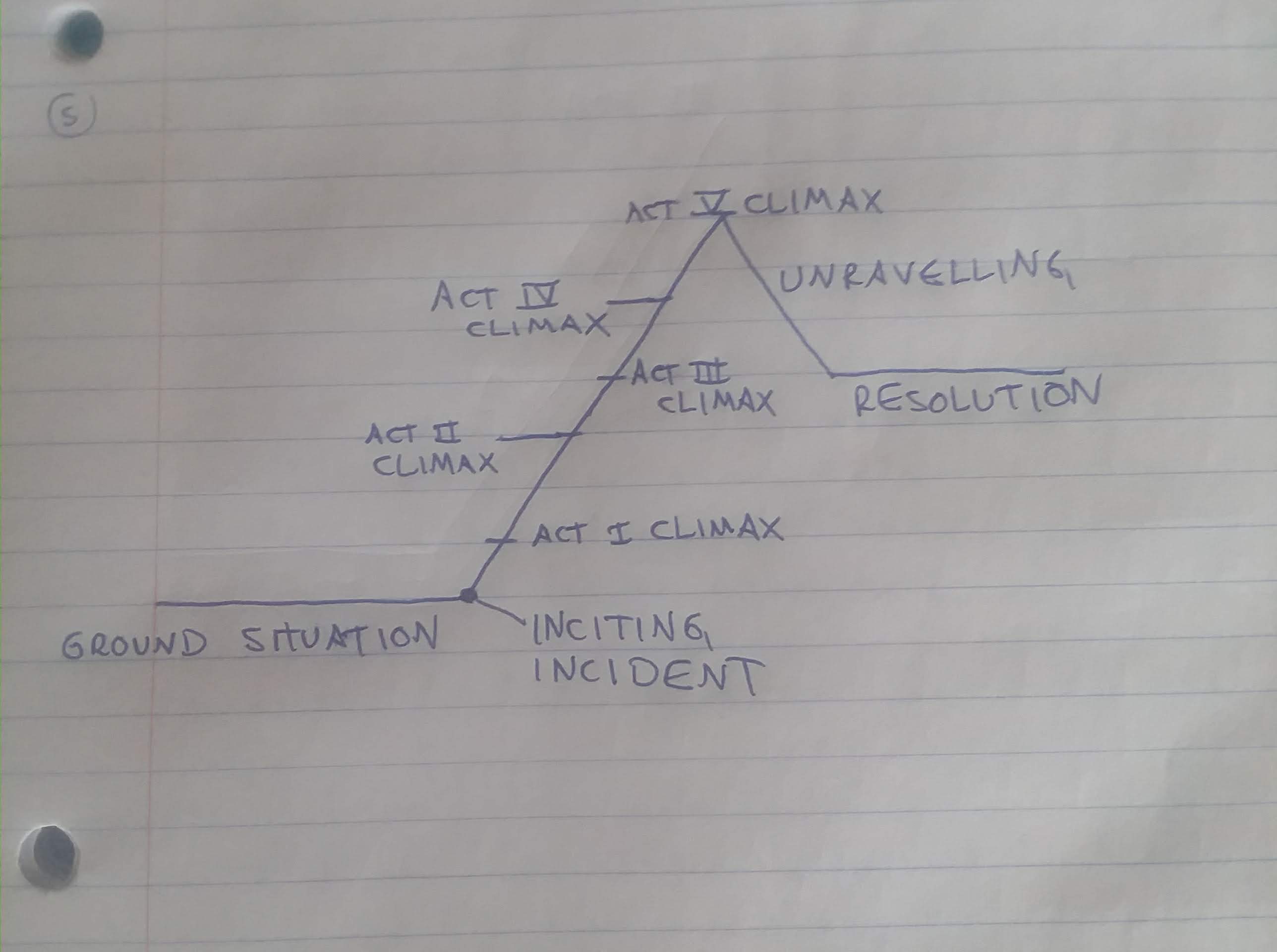

That is because each act has a climax (or reversal, or turn [bad to good, good to bad, etc.]).

Aristotle says that lengthier works need at least three turns to keep the audience interested (Walker’s one-page “The Flowers” needs only one), hence the three-act structure often found in movies and plays and novels (most of the novels I’ve taught are divided into three parts, or three books, or their number of chapters is divisible by three).

When we map this 3-act structure onto our modified triangle, it looks like this:

Three turns, probably alternating (good to bad to good, bad to good to bad, etc.).

Shakespeare’s structure is similar, but with more acts. Five turns, each building toward the final reversal in Act V:

So, right or wrong, the above is my new way of drawing Shakespeare’s 5-act structure. It makes sense to me. At least for now.

In our pew, after the third time I said, “Aristotle says,” Liz said that John Green says that Aristotle got almost everything wrong. I was about to say something in response, but the ceremony began.

CATE Conference 2018

A few weeks ago, Liz and I flew down to San Diego for our second CATE (California Association of Teachers of English) Conference.

Last year, the conference was in Santa Clara (a not-too-long drive for us), and we gave a presentation based on a chapter of our book, Method to the Madness. The presentation was titled, Creating Critical Thinkers through the Study of Literature (which is also our book’s subtitle).

This year, our presentation was based on another chapter of the book and was titled, Contemporary Short Fiction: the Key to Unlocking Potential and Leveling the Playing Field for Students of All Ability Levels (long title). We had given a longer version of the presentation to Tracy Unified School District in January.

The presentation began with the rationale for building curriculum centered on quality literature (fiction, poetry, drama, creative nonfiction). There was (still is?) a misconception that Common Core equals less literature in the English classroom and more “informational” reading. This, of course, is a misunderstanding that the framers of the standards have addressed: “Said plainly, stories, drama, poetry, and other literature account for the majority of reading that students will do in the high school ELA classroom. […]The Standards could not be clearer: ELA classrooms must focus on literature — that is not negotiable, but a requirement of high school ELA.” (David Coleman & Susan Pimental)

Next, Liz gave her pitch for using contemporary short stories in the English classroom, particularly as an opening unit, such stories being accessible to a variety of students (including those with attendance issues). These high-quality stories can be taught in a single class period (or two), and they offer students the opportunity to engage with a wide variety of voices while allowing the teacher the opportunity to establish (or remediate) essential skills.

We had prepared to use three short stories—Sticks by George Saunders, The Flowers by Amy Walker, and How to Talk to Your Mother (Notes) by Lorrie Moore—but we only got through the first two.

Each of those stories (Sticks and The Flowers) fits onto a single page, but each story is very meaty. We asked our participants to read and annotate each story, and, despite (as mentioned) each story being only one page, they each led to a wide-ranging academic discussion of the significant choices being made by the author.

(Note: all of the above was great, great, great, and a lot of fun, because our participants were so great, and also because Liz is so great at this.)

We ended with a discussion of narrative structure (the traditional plot curve, which is sometimes incorrectly perceived as a restraint to creativity and voice [a view I once embarrassingly held] but that instead allows for infinite variation).

We were getting short of our time, there were several slides to go, and I was sort of floundering, describing the plots of Pixar movies. Liz would later say that when I gave a third such example, she knew I was in trouble.

But a participant saved me by asking if, when learning about this narrative structure, which is so obvious in Pixar movies, students can apply the elements (ground situation, inciting incident, conflict, complications, climax, resolution) to something like The Flowers, which is so short and describes a single event.

This was exactly where, despite all floundering, we were supposed to be headed, and, as a group, we tried it. It turns out, despite being only one page and describing only one incident, The Flowers “fits” the narrative structure perfectly (infinite variation).

So, we modeled lessons on two one-page short stories (Sticks, by the way, Liz describes as the only “magic bullet” for English teachers: a two-paragraph story that students always like and always have so much to say about). Each story is accessible to a variety of students, and each story provides the opportunity for critical reading, critical thinking, analytical writing, and academic discussion.

Several people came up at the end to buy books (which was very nice), and a few told us that it was the best presentation they had been to all weekend (but maybe they say that to all the presenters).

Holiday Parties and The Dead

This essay will be published at Connotation Press: An Online Artifact on January 15th.

Teaching Native Son by Richard Wright, Part Three

The third part of my post on teaching Richard Wright’s 1940 novel, Native Son, is up at Method to the Madness: Creating Critical Thinkers through the Study of Literature (teachinglit.org). If you’d like to read it, please click here.

George Saunders

In the spring of 2008, I stood alone in a mostly empty hallway at Franklin High School, laughing out loud. There were a few people around, coming and going. They looked at me, as they came and went, in exactly the way you would expect someone to look at someone who was standing alone in a mostly empty hallway and laughing out loud.

I didn’t notice, though, or didn’t care. I was reading George Saunders’s 2000 story collection, Pastoralia, specifically the title story Pastoralia.

I was a teacher at Franklin High, just finishing my second year. I didn’t normally stand alone in mostly-empty hallways, reading. I had a classroom. But it was state testing time, and I was a rover.

Last week, I finished my tenth year at Franklin (of eleven years as a full-time teacher, one of those years spent elsewhere). Also last week, I read George Saunders’s first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, released earlier this year.

Though I’m not sure of the exact timeline, it wasn’t too long after reading Pastoralia and laughing out loud in the hallway in 2008, maybe even that same afternoon, that I started writing what would eventually become my MFA thesis and later my first (and so far, only) published novel, Parnucklian for Chocolate.

Those first-produced pages, though not nearly as good as Pastoralia, represented an attempt to emulate the unnamed qualities of Pastoralia that had made me laugh out loud in a mostly-empty hallway—to “sound” like Pastoralia, and to “sound” like Saunders.

The following paragraph—one of the first I wrote of Parnucklian—is an example of a paragraph that, though not as good as Saunders, attempts to sound like Saunders:

“The planet Parnuckle,” Josiah’s mother would often continue, “which is the home planet of your father, and therefore is your home as well, will always be your home, even though you have never been there, and possibly never will, but it will always be there as your home, because it is the home of your father, just like this home, which is my home, and also your home, is also your home, even if you grow up and move far away, as long as you live, or unless I move to another home, but then that home will also be your home. Your father, on the other hand, will never leave Parnuckle, so that will not be an issue. Of course, that’s not quite fair, as it’s comparing a house on a planet to a planet. I, likewise, will never leave this planet, nor will this house, or any house I may be living in, either in the future or whenever.”

Five springs later, at the 2013 AWP Conference in Boston, the week of Parnucklian’s release, I told George Saunders, who had happened to sit down at the same otherwise-empty common area table as me, first politely asking my permission—I, staring up at George Saunders, initially unable to respond, eventually doing so in eighth-grade-girl-meets-lead-singer-of-favorite-band fashion—in the first of two conversations I have had with George Saunders (one digital, one not; description of latter commencing, former forthcoming—said conversation being one that George Saunders probably immediately forgot but that for me has become a commonly repeated anecdote) that (predicate of current sentence now proceeding) when I had written early drafts of just-released-novel-I-was-there-in-Boston-to-promote I had been reading a lot of his work, specifically Pastoralia, and that, at least in the early drafts, I had tried to “sound” like him, specifically like Pastoralia.

He had responded that that was fine.

Reading Pastoralia in 2008 had not been my first encounter with Saunders’s work. In 2000, while at Cal Poly, I took a fiction writing course that, for a few reasons, would be fairly influential in regards to my later becoming a creative writing grad-student and fiction writer, one of those reasons being exposure to writers of literary fiction the likes to which I had never been exposed before—had never before read literary fiction, in fact before taking this class had never even heard of literary fiction—such as TC Boyle, Lorrie Moore, and the recently-departed Denis Johnson. And also George Saunders. Of the first three, our instructor assigned books—If the River was Whiskey, Self-help, and Jesus’ Son, respectively—but of Saunders the instructor gave us Xeroxed copies of The Barber’s Unhappiness. I’d never read anything like it. I immediately wrote a terrible now-lost story that tried to copy it (around that same time, I also wrote a lot of terrible now-lost stories that tried to copy the stories in Jesus’ Son).

Half-a-dozen years later, I stumbled across another Saunders story: Sticks. The story would later be collected in his 2013 book, The Tenth of December, but back then the story was just on his website, which looked exactly the way websites used to look in the mid-aughts.

By then I had started teaching. I copied the story into a Word document. Back then, I used to spend my lunch break eating cheeseburgers and sort-of-frantically searching for something to do with the next two classes. That day, I used Sticks, and over the next eleven years I would use the story in a variety of different lessons. It was perfect for it: short (just two paragraphs) but meaty.

In 2013, at AWP, after the awkward silence that had followed George Saunders telling me that it was fine that at least in early drafts of my recently-released-novel-I-was-there-to-promote I had tried to “sound” like him, I told George Saunders that it had been nice to see that Sticks had been included in the new book. I then proceeded, in a sort of confession, to tell George Saunders that over the previous seven years I had without permission or payment made hundreds and hundreds of copies of his story Sticks and had distributed the story to hundreds and hundreds of teenagers for use in a variety of different lessons, it being a perfect fit for such: so short but so meaty.

He, who is every bit as nice as everyone says he is, responded that that was fine.

In fact, he wrote his email address in my AWP program and told me to have students email him if they had any questions about the story.

In 2015, when my wife, who is also a teacher and whom I met at Franklin High and who over the past decade has also used Sticks in a variety of different lessons, and I spent three months co-authoring a book on teaching literature in high school, we included a lesson on Sticks (this time paying for permission).

Before the book’s publication, our editor had instructed us to seek out blurbs and a foreword.

We sent emails to a lot of education-y people. But we also thought: why not email the famous living authors of stories we had referenced in the book. So we emailed Junot Díaz and George Saunders. We wrote what we considered to be a professional but folksy message with plenty of flattery aimed at the recipient.

Junot Díaz did not respond. But George Saunders did.

He said that he couldn’t tell us how much he appreciated us teaching Sticks. He said that he wished he could be more helpful, but he didn’t have time to write a foreword or a blurb. He said that he was writing like mad.

I replied by thanking him for his response. And I said that as one of his devoted readers, I was looking forward to whatever it was that he was working on.

He was working on Lincoln in the Bardo, which I read last week, in three days (I don’t normally read books in three days—more like three months; in fact, I hadn’t yet read the book, which Liz had bought me for Valentine’s Day, because it took me all those months to finish reading John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor).

Lincoln in the Bardo is fabulous. It’s different—definitely a bit weird—but good. You should read it. Sometimes, it’s very, very sad. But at other times it’s very funny. It may even make you laugh out loud.

Mind Your Business!

Day before yesterday, at the zoo, where I had taken my wife and two sons, I turned to a man—about my size though perhaps a touch older but definitely less round in the middle—and told him—sternly, aggressively—to mind his own business.

When the man just sort of stared back, I stood, having theretofore been seated on a bench, the man likewise on the next bench over, and, standing, I told him again.

The previous evening, I had given my wife a draft of a story that I had been working on and that I had just finished (or at least had just finished drafting). The story’s protagonist is named Bob Sanders, and I’ve used Bob Sanders as the protagonist in two other stories. Bob Sanders is sort of a version of myself. Just sort of.

The story takes place at Disneyland (and we just so happen to be going to Disneyland in two weeks), and early in the story Bob—along with his wife, Linda, and son, Bobby Jr.—is kicked out of Disneyland when Bob gets into a row with another man at Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln. Twelve years later, Bob—now along with his wife and three sons (one teenager, two toddlers) plus his aunt—is kicked out again for a row at the Disney Jr. live show.

In the first row, violence is threatened. In the second, the story’s climax, it is enacted.

Said climax gets going like this:

The man behind Bob and Little Stevie and Just Teddy loud-whispered to his wife, “This. Is. Ridiculous.” It was hard to hear what the puppets were saying over Just Teddy’s screaming and gasping. The woman loud-whispered back to her husband, “Maybe he should take him outside.” Then the man touched Bob on the shoulder and loud-loud-whispered, to Bob, “Maybe you should take him outside.”

Bob immediately turned back to the man and said, “Mind your business.” Bob had just known that that man or that woman were going to say something, and he had been all ready to tell him or her or them to just mind their business.

After telling the man to mind his business, Bob stared at the man, longer than before. The man stared back, then looked over Bob at the puppets.

Then it escalates from there.

While reading the story, my wife, Liz, said: “I like that he’s you but so much worse.” Which is kind of the point.

But she also said, “I’m so nervous for his wife.” In fact, the story and its disastrous events made Liz so nervous about our upcoming trip to Disneyland that she had to put it down for a while.

At which point I reiterated, as I have had to do before, that Bob is not me. That they are not us. That it’s all made up. It’s fiction.

Then came the zoo, the following morning, where Liz looked up from monitoring a five-year-old and a two-year-old on the playground structure to see her husband standing, looming over another man and loudly (though I don’t remember saying it loudly though it was loud enough for Liz to hear across the screaming-kid-populated playground) telling the man to mind his own business.

Here’s what the man had done:

So there were all these kids and mostly they were going down the slide and before I go any further let me say that this guy was sort of this Oh I’m so much cooler than everyone else ever and I’m a grown man who wears board shorts to the zoo and uses hair gel so anyway for whatever reason this guy is like making these like scoffing noises clearly directed at all the not-as-cool other parents including at Liz and then at one point Sam our two-year-old stops at the top of the slide and holds up the line and this girl who turns out to be his daughter is behind Sam and this guy does his scoff sound again (the best way to describe this sound is that it’s the sound that the popular jock who actually hates himself makes throughout the preview of the school play that his teacher brought his class to) and then the guy mutters Just go and by the way the muttering-tone of this grown man in board shorts is that of a twelve-year-old girl and Sam ends up not going down the slide and Liz like has to go up and get him and then the guy’s daughter goes and that’s when it started to get weird because this girl goes down the slide and says something to the effect of Didja see, Daddy? and then this guy just announces to who-knows-who “I don’t micromanage that crap” and then a minute later the girl is up there again and shouts something like Watch me, Daddy! and then the guy says “You know the drill; I don’t micromanage that shit” the implication obviously being that the rest of us not-in-board-shorts parents were un-cool micromanagers. It helps if when you’re imagining all of this, if you are, the guy is sort of slouched down on the bench, with his legs spread as wide as humanly possible.

And then another dad waited for and caught his toddler at the bottom of the slide, and the scoffer scoffed again and teenage-girl-muttered Just let him go. And I’d heard enough from this jackass. And I turned to him and told him—sternly, aggressively—to mind his own business. And when he just stared back, I stood up and told him again.

Was I cognizant of the fact that I had turned to a man and had said the exact same thing that in the lead-up to a violent and climactic fictional moment was also said by Bob Sanders, who I had the night before insisted to my nervous wife was fictional and not representative at all of my own behavior, or potential behavior?

No. Not at all. Liz had done exactly the right thing in reacting to the aforementioned image of my looming and had grabbed both of our children for a quick exit.

As I followed her off the playground, claiming that it was all fine because the guy didn’t do anything, he just sat there and looked away, I didn’t picture myself as Bob Sanders. A hybrid of Captain Call and Madison Bumgarner, rather, forcing everyone by threat of violence to behave themselves.

Liz had to explain the obvious later, in the car.

She didn’t get mad, though, about any of it. Which is perhaps more than I deserve.