In the spring of 2008, I stood alone in a mostly empty hallway at Franklin High School, laughing out loud. There were a few people around, coming and going. They looked at me, as they came and went, in exactly the way you would expect someone to look at someone who was standing alone in a mostly empty hallway and laughing out loud.

I didn’t notice, though, or didn’t care. I was reading George Saunders’s 2000 story collection, Pastoralia, specifically the title story Pastoralia.

I was a teacher at Franklin High, just finishing my second year. I didn’t normally stand alone in mostly-empty hallways, reading. I had a classroom. But it was state testing time, and I was a rover.

Last week, I finished my tenth year at Franklin (of eleven years as a full-time teacher, one of those years spent elsewhere). Also last week, I read George Saunders’s first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, released earlier this year.

Though I’m not sure of the exact timeline, it wasn’t too long after reading Pastoralia and laughing out loud in the hallway in 2008, maybe even that same afternoon, that I started writing what would eventually become my MFA thesis and later my first (and so far, only) published novel, Parnucklian for Chocolate.

Those first-produced pages, though not nearly as good as Pastoralia, represented an attempt to emulate the unnamed qualities of Pastoralia that had made me laugh out loud in a mostly-empty hallway—to “sound” like Pastoralia, and to “sound” like Saunders.

The following paragraph—one of the first I wrote of Parnucklian—is an example of a paragraph that, though not as good as Saunders, attempts to sound like Saunders:

“The planet Parnuckle,” Josiah’s mother would often continue, “which is the home planet of your father, and therefore is your home as well, will always be your home, even though you have never been there, and possibly never will, but it will always be there as your home, because it is the home of your father, just like this home, which is my home, and also your home, is also your home, even if you grow up and move far away, as long as you live, or unless I move to another home, but then that home will also be your home. Your father, on the other hand, will never leave Parnuckle, so that will not be an issue. Of course, that’s not quite fair, as it’s comparing a house on a planet to a planet. I, likewise, will never leave this planet, nor will this house, or any house I may be living in, either in the future or whenever.”

Five springs later, at the 2013 AWP Conference in Boston, the week of Parnucklian’s release, I told George Saunders, who had happened to sit down at the same otherwise-empty common area table as me, first politely asking my permission—I, staring up at George Saunders, initially unable to respond, eventually doing so in eighth-grade-girl-meets-lead-singer-of-favorite-band fashion—in the first of two conversations I have had with George Saunders (one digital, one not; description of latter commencing, former forthcoming—said conversation being one that George Saunders probably immediately forgot but that for me has become a commonly repeated anecdote) that (predicate of current sentence now proceeding) when I had written early drafts of just-released-novel-I-was-there-in-Boston-to-promote I had been reading a lot of his work, specifically Pastoralia, and that, at least in the early drafts, I had tried to “sound” like him, specifically like Pastoralia.

He had responded that that was fine.

Reading Pastoralia in 2008 had not been my first encounter with Saunders’s work. In 2000, while at Cal Poly, I took a fiction writing course that, for a few reasons, would be fairly influential in regards to my later becoming a creative writing grad-student and fiction writer, one of those reasons being exposure to writers of literary fiction the likes to which I had never been exposed before—had never before read literary fiction, in fact before taking this class had never even heard of literary fiction—such as TC Boyle, Lorrie Moore, and the recently-departed Denis Johnson. And also George Saunders. Of the first three, our instructor assigned books—If the River was Whiskey, Self-help, and Jesus’ Son, respectively—but of Saunders the instructor gave us Xeroxed copies of The Barber’s Unhappiness. I’d never read anything like it. I immediately wrote a terrible now-lost story that tried to copy it (around that same time, I also wrote a lot of terrible now-lost stories that tried to copy the stories in Jesus’ Son).

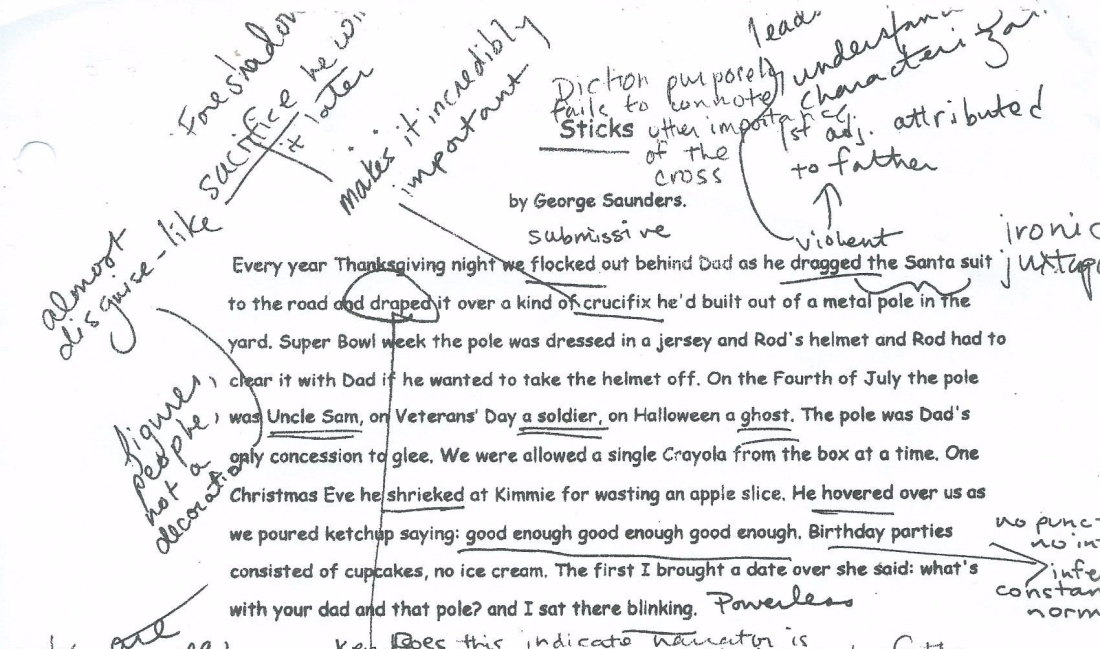

Half-a-dozen years later, I stumbled across another Saunders story: Sticks. The story would later be collected in his 2013 book, The Tenth of December, but back then the story was just on his website, which looked exactly the way websites used to look in the mid-aughts.

By then I had started teaching. I copied the story into a Word document. Back then, I used to spend my lunch break eating cheeseburgers and sort-of-frantically searching for something to do with the next two classes. That day, I used Sticks, and over the next eleven years I would use the story in a variety of different lessons. It was perfect for it: short (just two paragraphs) but meaty.

In 2013, at AWP, after the awkward silence that had followed George Saunders telling me that it was fine that at least in early drafts of my recently-released-novel-I-was-there-to-promote I had tried to “sound” like him, I told George Saunders that it had been nice to see that Sticks had been included in the new book. I then proceeded, in a sort of confession, to tell George Saunders that over the previous seven years I had without permission or payment made hundreds and hundreds of copies of his story Sticks and had distributed the story to hundreds and hundreds of teenagers for use in a variety of different lessons, it being a perfect fit for such: so short but so meaty.

He, who is every bit as nice as everyone says he is, responded that that was fine.

In fact, he wrote his email address in my AWP program and told me to have students email him if they had any questions about the story.

In 2015, when my wife, who is also a teacher and whom I met at Franklin High and who over the past decade has also used Sticks in a variety of different lessons, and I spent three months co-authoring a book on teaching literature in high school, we included a lesson on Sticks (this time paying for permission).

Before the book’s publication, our editor had instructed us to seek out blurbs and a foreword.

We sent emails to a lot of education-y people. But we also thought: why not email the famous living authors of stories we had referenced in the book. So we emailed Junot Díaz and George Saunders. We wrote what we considered to be a professional but folksy message with plenty of flattery aimed at the recipient.

Junot Díaz did not respond. But George Saunders did.

He said that he couldn’t tell us how much he appreciated us teaching Sticks. He said that he wished he could be more helpful, but he didn’t have time to write a foreword or a blurb. He said that he was writing like mad.

I replied by thanking him for his response. And I said that as one of his devoted readers, I was looking forward to whatever it was that he was working on.

He was working on Lincoln in the Bardo, which I read last week, in three days (I don’t normally read books in three days—more like three months; in fact, I hadn’t yet read the book, which Liz had bought me for Valentine’s Day, because it took me all those months to finish reading John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor).

Lincoln in the Bardo is fabulous. It’s different—definitely a bit weird—but good. You should read it. Sometimes, it’s very, very sad. But at other times it’s very funny. It may even make you laugh out loud.