I have an essay on Shakespeare’s Five-Act Structure in the February issue of California English. Here’s a link: https://cateweb.org/journals/february-2019/

Tag: shakespeare five act structure

Rethinking Shakespeare’s 5-act Structure

For most of my twelve years teaching high school English, I’ve taught a lesson on the 5-act structure of Shakespeare’s plays.

I even put it in a book.

But I don’t think any of it is right.

Two weeks ago, as we waited in a church pew for our oldest son’s preschool graduation ceremony to begin, my wife, Liz, and I got into a debate about the climax of Hamlet, said debate beginning with my above-repeated admission that what I’ve been saying to students about Shakespeare’s 5-act structure I no longer believe to be true.

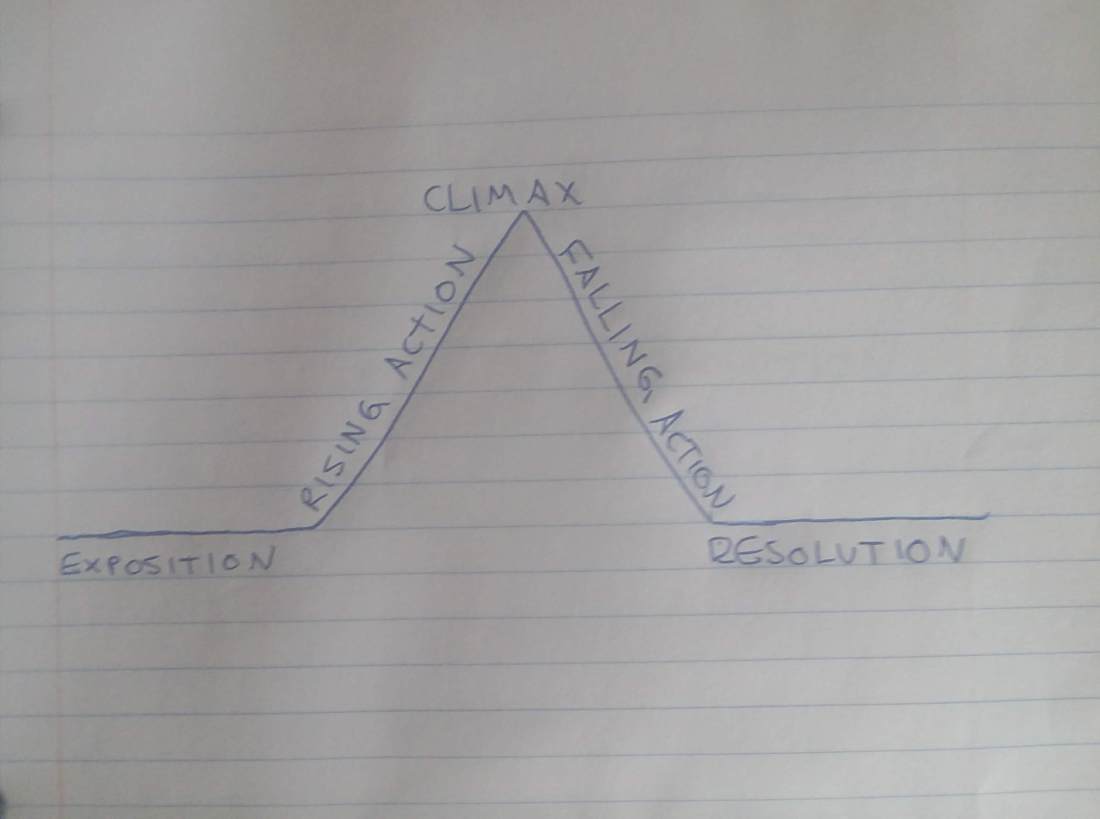

What I’ve been saying—off and on for twelve years—and what I also included in a chapter on Taming of the Shrew in our book, Method to the Madness: A Common Core Guide to Creating Critical Thinkers through the Study of Literature (co-written by Liz and me; she wrote the Hamlet chapter), is that Shakespeare’s 5-act structure can be roughly mapped onto the familiar plot diagram as follows:

Act I = Exposition

Act II = Rising Action/Complications

Act III = Climax

Act IV = Falling Action

Act V = Resolution/Denouement

I, of course, am not the first nor the only teacher to teach this. It all started with Gustav Freytag, a 19th-century German novelist and playwright, who diagrammed the five story parts above (exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution) using a triangle, now known as Freytag’s Pyramid, which looks like this:

As an example, Freytag mapped the 5-act structure of a Shakespeare play onto his pyramid (said mapping making its way from Freytag through generations of teachers and teacher resources to me, around twelve years ago, and on to my students, some of whom now teach, and into an additional teacher resource, co-written by me).

The last couple of times that, out of habit, I drew the above diagram on my whiteboard, I knew there was something wrong with it.

This was perhaps because it did not square at all with the diagram I had been drawing for students during my short fiction unit.

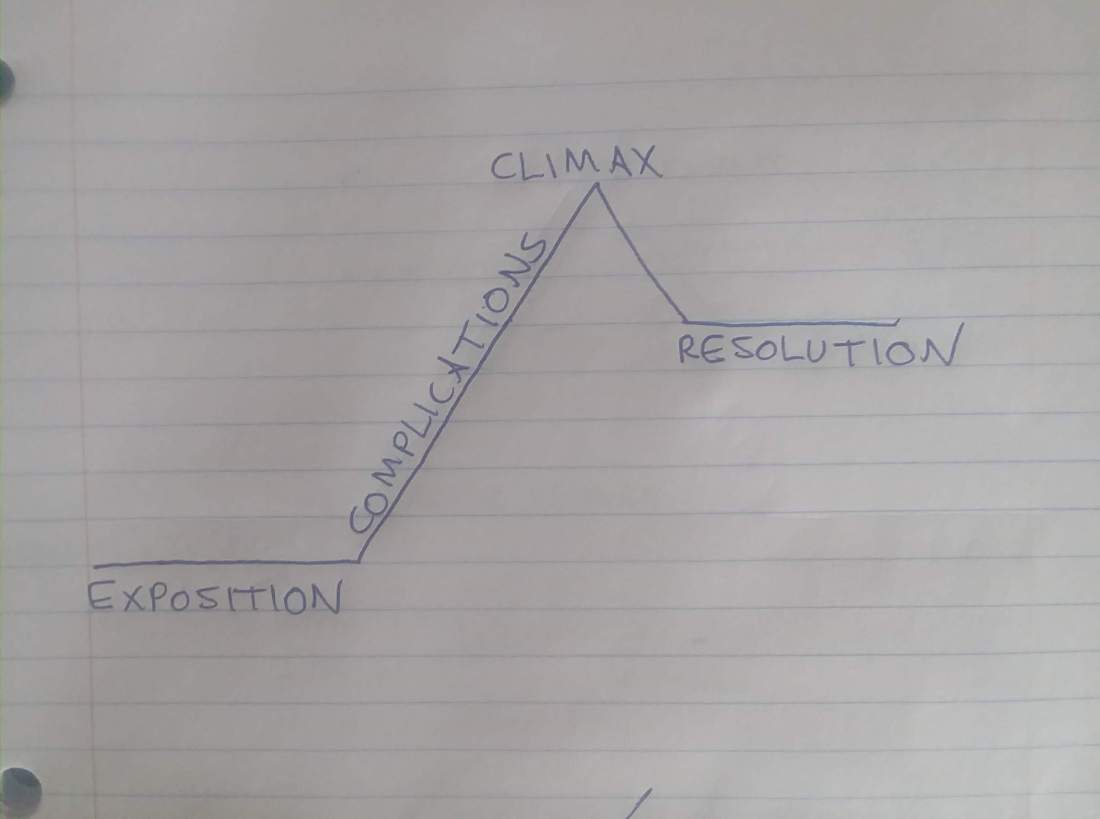

About halfway through my teaching career, I figured out that Freytag’s Pyramid, as shown above, is problematic when applied to fiction writing, particularly short stories, and particularly when trying to help students draft well-plotted short stories.

I started drawing this, instead:

The biggest difference between Freytag’s diagram and this one is the latter’s lack of symmetry (reason to follow).

A similarity is that they both begin and end with a flat line.

The flat line on the left-hand side represents the ground situation (I also discovered, about halfway through my teaching career, that I’d been teaching exposition wrong, telling students that it’s the part of the story in which the author introduces the setting, the characters, and the conflict. All of that is true, but what is more helpful to students who are drafting stories is to tell them that the exposition has two vital components: the ground situation [the state of things, often teeming with potential conflict, before the conflict is incited] and the inciting incident [just what it sounds like: an incident, often but not always the addition of a character, that incites the conflict and sends the previously flat-lined diagram angling upward]).

The flat line on the right-hand side represents the new state of affairs after the conflict has been resolved and the knot unraveled.

This post-denouement state of affairs does not/should not/cannot return to the same state of affairs represented by the ground situation. A change must have occurred, otherwise no story has been told, hence the lack of symmetry in the latter triangle (this is not original; it is a modification to Freytag’s triangle suggested by John Barth in his metafictive story, “Lost in the Funhouse” [and probably elsewhere, too, by others]).

The other big difference between the two triangles is the elimination, in the latter, of the falling action, one discovering when studying (or simply consuming) stories that the resolution often comes on the heels of the climax (another reason for the lack of symmetry: there is usually much more story before the climax than there is after it).

What I like to say to students about the above-drawn diagram is that it is a formula that allows for infinite variations. It is inexhaustible. And it is.

I said the same thing to a roomful of teachers at February’s CATE Conference, where Liz and I were leading a workshop on teaching contemporary short fiction.

After I had said the above and had used one too many Pixar movies as an illustration, a participant, as a sort of friendly challenge, asked if we could apply the same structure to “The Flowers” by Alice Walker (a one-page story describing a single incident), which we had earlier in the workshop read on the lookout for concrete details.

I wasn’t prepared for such a challenge, nor had I previously attempted the suggested application, but the clever teachers in the room quickly discovered, despite all of the differences between “The Flowers” and Finding Nemo, that the structure did indeed fit both. Perfectly.

So, then: Shakespeare.

Liz’s and my church pew debate came at the end of a week in which I had listened to dozens of high school juniors, during their oral examinations, explain that the Mousetrap (Hamlet’s play-within-the-play, manufactured to reveal Claudius’s guilt) is the climax of the play.

When, in our pew, I asked Liz what the climax of the play is, she answered that it is the Closet Scene, particularly Hamlet killing Polonius.

The students’ reasons were fuzzy (for many, they were unstated altogether; the reason that was the climax was that their English teacher had said so).

Liz’s reasoning, on the other hand, was fully- and well-articulated (she is brilliant in many many things, but particularly astute when discussing Hamlet): that, to poorly paraphrase, by killing Polonius (believing he is killing Claudius) Hamlet demonstrates the resolution that, two acts later, allows for resolution.

Both the students’ and Liz’s proposed climaxes occur in Act III (scenes 2 and 4, respectively) and therefore fit the Freytag map of Shakespeare’s 5-act structure.

Freytag supposedly leaned heavily on Aristotle, but it is precisely the lessons in Poetics that lead me to question Freytag and my own previous teaching.

Aristotle says that the Complication (what we often call the Rising Action) is a causal sequence of story events (or scenes) in which, scene to scene, the stakes (and thereby drama) increase and increase until we arrive at the climax (which Aristotle describes as a reversal in fortune [bad to good, good to bad, etc.]).

After this final reversal, Aristotle says, there is nothing but the unraveling.

How, then, can this causal sequence reach its peak in Act III, with two acts to go?

From our pew, I argued that the climax of Hamlet is the duel in Act V. It all builds to that. Hamlet dies (final reversal), after which there is only the unraveling (Fortinbras takes over, honors Hamlet, etc.).

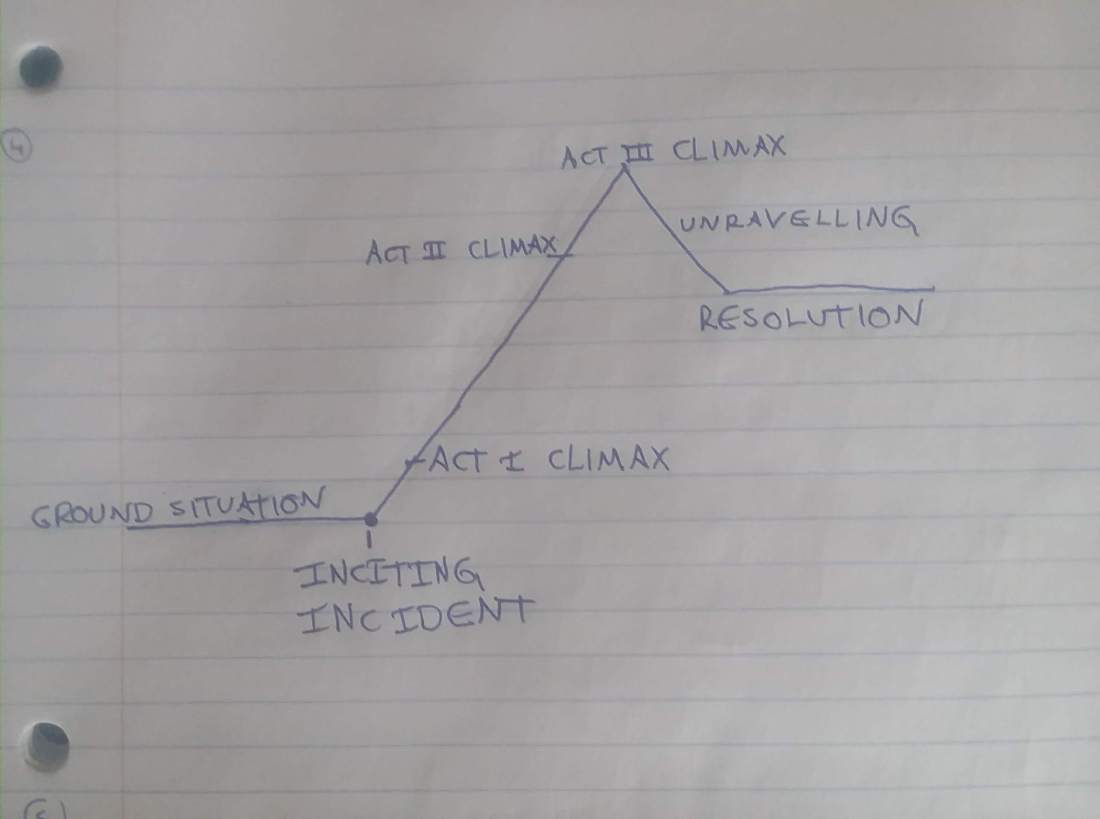

Freytag, those juniors, and Liz are right about one thing, though: Act III is climactic.

That is because each act has a climax (or reversal, or turn [bad to good, good to bad, etc.]).

Aristotle says that lengthier works need at least three turns to keep the audience interested (Walker’s one-page “The Flowers” needs only one), hence the three-act structure often found in movies and plays and novels (most of the novels I’ve taught are divided into three parts, or three books, or their number of chapters is divisible by three).

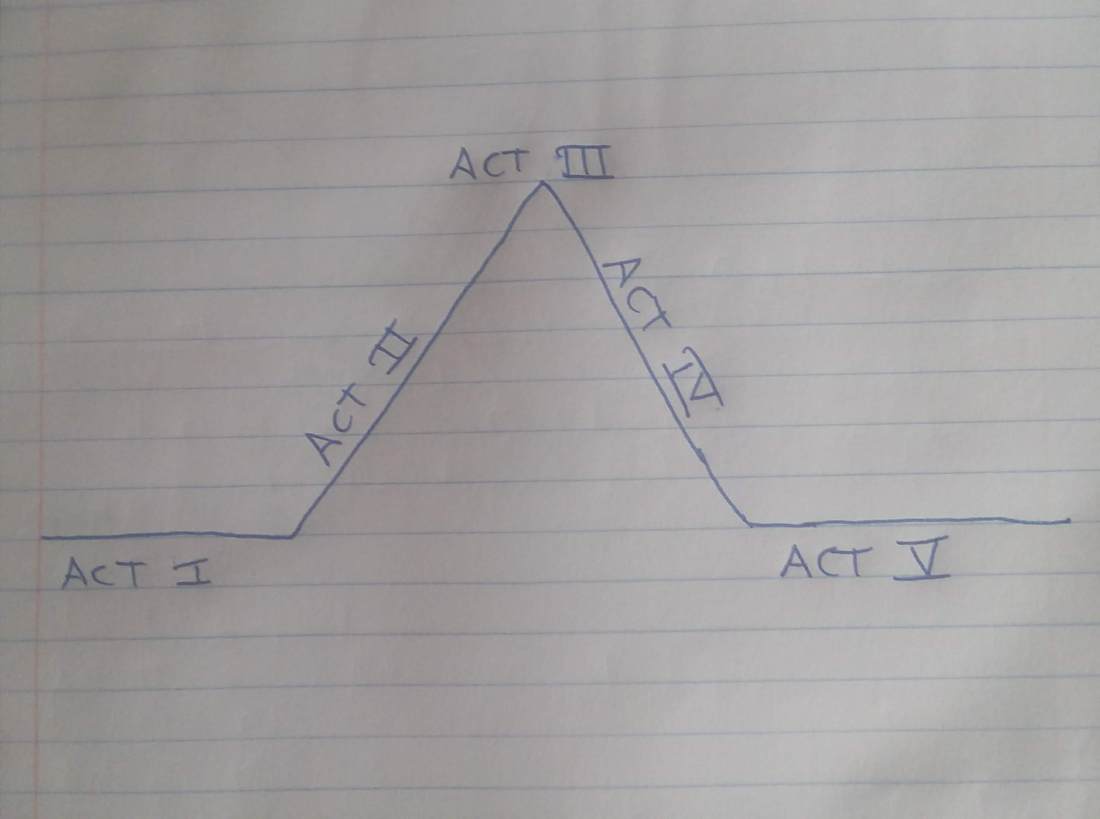

When we map this 3-act structure onto our modified triangle, it looks like this:

Three turns, probably alternating (good to bad to good, bad to good to bad, etc.).

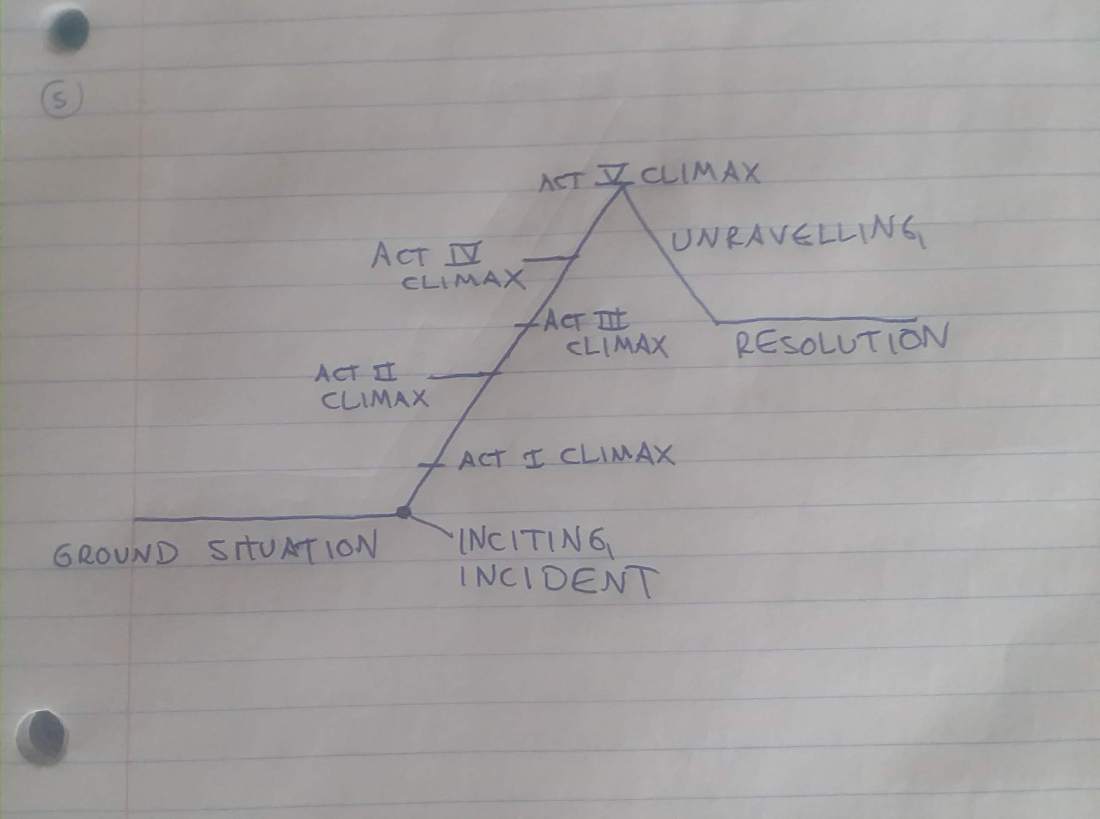

Shakespeare’s structure is similar, but with more acts. Five turns, each building toward the final reversal in Act V:

So, right or wrong, the above is my new way of drawing Shakespeare’s 5-act structure. It makes sense to me. At least for now.

In our pew, after the third time I said, “Aristotle says,” Liz said that John Green says that Aristotle got almost everything wrong. I was about to say something in response, but the ceremony began.